What’s a sheep worth?

Sheep have come to dominate the Scottish landscape, but at what cost? We could produce all the lamb we need while also supporting farmers to restore our lost biodiversity, but if farmers insist they cannot coexist with native species, it’s surely time to ask: what are sheep really worth, and do we need so many?

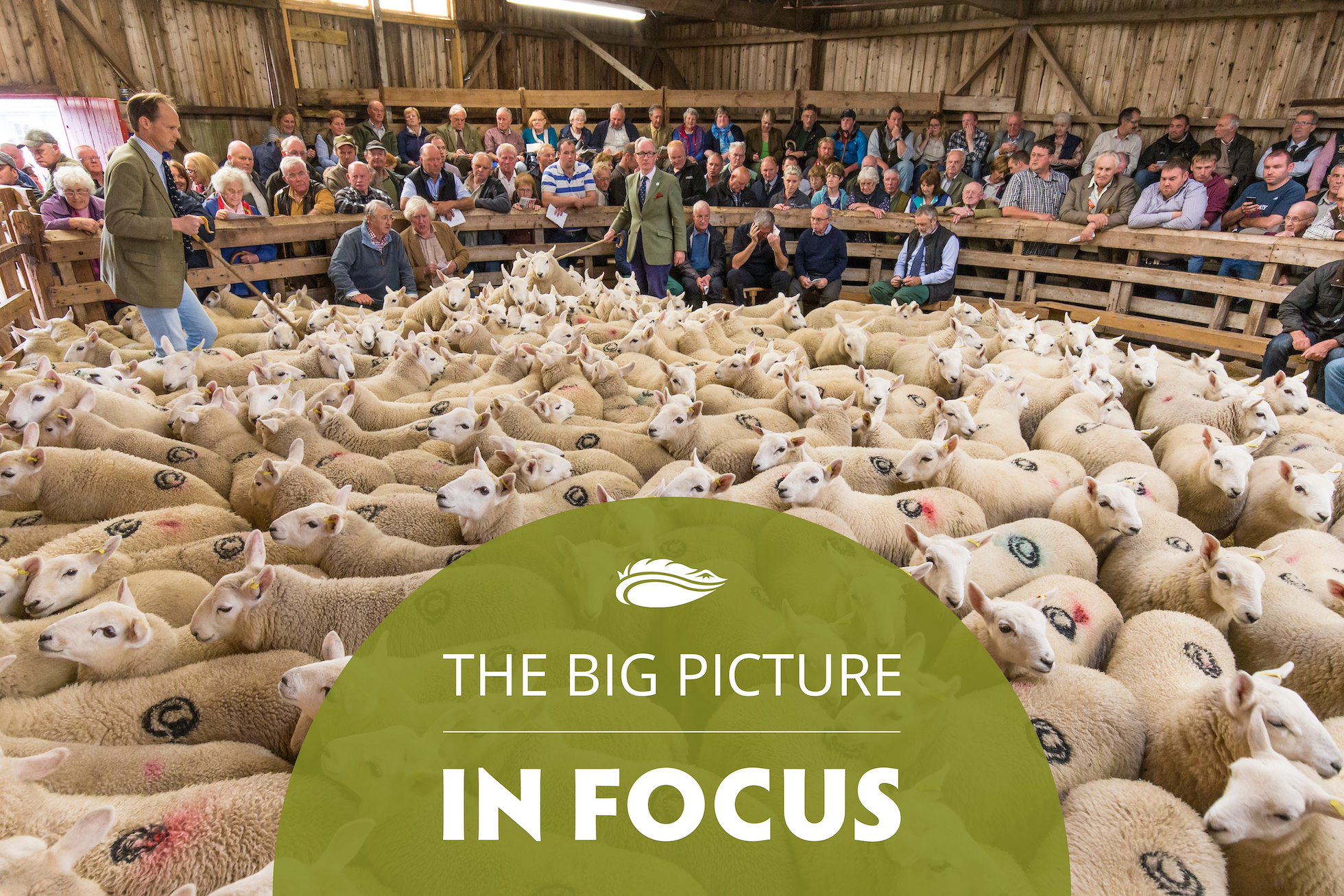

Part of our ‘The Big Picture in Focus’ series, providing a deep dive into the stories that impact Scotland’s road to nature recovery.

On a recent sunny Sunday, I took the opportunity to walk up Càrn a’ Chlamain, approaching the snowy summit via Glen Tilt to take in what is often described as one of the Highlands’ most beautiful glens. Certainly, it is pretty in places and the river is beautiful. But if you enjoy spotting wildlife, the walk may be a disappointment. Across more than 6 hours and 16 miles I saw just one buzzard, one raven, one red squirrel and two robins. The only animals I saw in abundance were sheep.

‘Today, Scotland supports some of the highest densities of sheep in the world, but it wasn’t always so.’

I wasn’t really searching for wildlife. I could perhaps have sat and scanned for the mountain hare that had left its tracks pressed in the snow. But the sheep were unavoidable, sorry-looking animals shuffling around ring feeders or staring vacantly into space, their dirty wool caught on every nibbled shrub, their dung trampled into the track. For anyone who walks much in Scotland, this is a familiar experience, for ours has become a land of sheep.

Today, Scotland supports some of the highest densities of sheep in the world, but it wasn’t always so. Until the 19th century, cattle dominated Scottish rural life within a patchwork landscape that supported a more evenly distributed human population and much greater agricultural variety. It was only after the arrival of ‘big sheep’, such as the Cheviot and Blackface breeds, that cattle began to be squeezed out, followed by the people who lived with them. High wool prices then accelerated the removal of people, as landowners sought to replace tenants with their increasingly profitable sheep.

At first, this takeover met with resistance, with many Highlanders reportedly viewing the invasive sheep as ‘an innovation not to be tolerated’. In 1792, the infamous Year of the Sheep, tenant farmers from Strathrusdale drove thousands of sheep off the land surrounding Ardross, with their protest only quashed by the dispatch of three companies of the Black Watch. A poem written in the same period by the Glengarry bard, Ailean Dughallach, laments:

Chan fhaicear ach caoraich is uain,

Goill mun cuairt daibh air gach silos

Tha gach fearann air dol fàs

Only sheep and lambs are visible,

Lowlanders surrounding them on every slope

All the lands have gone to waste

And yet, over time, sheep have become an accepted and even celebrated part of Scottish rural life, so that today, their presence is protected in the name of ‘cultural tradition’ and nothing is allowed to challenge their ubiquity. In the new, relatively sterile sheepscapes that have emerged, people are much removed, wildlife has nowhere to hide, and water can only sluice off the stripped hills and close-cropped fields, straight into our swollen rivers.

Now, beavers are attacked for felling the last few trees that have escaped the hungry mouths of millions of sheep and deer, while resentment grows against returning sea eagles, and everything from badgers to wild boar can be blamed for killing unsupervised lambs. Even without eagles or boar to reckon with, an endless war is waged against foxes, crows and ravens, while sheep farmers and their representatives present the biggest barrier to popular hopes for a transformative lynx reintroduction. And don’t anyone dare speak of wolves!

From the late 18th century, the growing dominance of sheep and the disappearance of humans hastened the decline of Scotland’s ancient shieling system, together with the natural diversity the older system had sustained.

Are sheep so important that their needs must always trump everything else, including government targets for nature recovery? Why must farmers’ apparent intolerance of any threat to their stock be allowed to preclude the return of valuable animals like lynx? What is it that makes sheep so special?

Certainly, for some people, sheep are very important. Beyond their market worth, the true value of a sheep for many farmers reflects a complex mix of financial imperatives, personal values and emotional motivations, often tied to generations of tradition. Some farmers maintain sheep flocks at a financial loss: they don’t do it for the money, but rather because their parents and grandparents did it. Rearing sheep is in their blood and a part of their identity. When sheep are lost, they are mourned as a cultural loss as much as an economic one.

‘Rearing sheep is in their blood and a part of their identity.’

Some farmers must also maintain minimum sheep numbers to meet the terms of tenancy contracts or qualify for financial support schemes. Others worry that fewer sheep could result in higher numbers of ticks, or a greater risk of fire on ungrazed hillsides. Some even wonder whether biodiversity might suffer if grazing regimes are changed, while the stratified nature of Scottish sheep farming – which uses sheep from the uplands to increase the vigour of lowland flocks – adds to the value of hill sheep.

On the other hand, hill farming poses challenges to sheep welfare. Hill sheep are not as closely supervised as lowland animals and the shepherd to ewe ratio is often very low. As a result, hill sheep suffering from injury, parasitism or disease do not always enjoy early assistance, while predation and poor nutrition in these harsher environments take an added toll.

‘Do we really need so many sheep, grazing so much of our land?’

There are questions too around the environmental impact of Scotland’s 6.8 million sheep. It is widely accepted that overgrazing by deer is damaging peat bogs and stifling the growth of new woodland, but nationwide sheep outnumber deer by around seven to one. And while carefully managed sheep grazing can theoretically support grassland biodiversity, many farmers have shifted from permanent grasslands to highly fertilised ryegrass pastures, which increase productivity but provide far less support for wildlife.

High densities of grazing animals, whether deer or sheep, make it harder for native woodland to regenerate.

Recent research also adds to growing concerns that sheep may be harming threatened ground-nesting birds. Many of our breeding waders rely on farmland – there is, after all, little else in Scotland – but the Working for Waders Nest Camera Project has revealed some surprising results.

In a small study of 87 wader nests across Scotland, predation was the leading cause of nest failure – no surprise there. In landscapes stripped of natural cover, nests in heavily grazed pastures will be exposed to every predator out there. But the top predator was unexpected: sheep. Cameras showed that 30% of predated nests had been raided by sheep, more than by badgers, foxes, or crows, while trampling and disturbance added to the losses.

Hillsides freed from intense grazing can re-wood naturally, slowing the flow of water off the hill, and reducing the risk of flooding and erosion.

Do we really need so many sheep, grazing so much of our land? Today, 55% of all Scotland's agricultural land – an estimated 3.6 million hectares – is used for upland sheep farming or mixed sheep and beef cattle. Even more land is used to produce the supplements fed to sheep when they need more than just grass – land that could be used to grow crops to feed us! In return, the sheep farming sector contributes a mere 7% of the total national income from farming, valued at £196 million in 2015. By comparison, Scotland’s soft fruit sector had an estimated worth of £128 million in 2015, generated across only 2200 hectares – less than 1% of the land used for agriculture.

‘We could cut production by over 40% and still produce all the sheep meat we consume.’

Meanwhile, the percentage of livestock farms that depend on support payments is increasing, with Scottish Government data published in March 2024 revealing that without these payments, just 8% of sheep farms in Less Favoured Areas (LFAs) would make a profit. And these areas are not the exception to the rule. LFAs make up over 85% of Scottish agricultural land and support 90% of our sheep. The NFUS itself says: ‘The value of extensive production systems, and their products, is generally not sufficiently rewarded by the market to render them economically viable without financial support.’

It’s true that much of the land used to graze sheep is unsuitable for other types of farming. And it might be worth the investment of land and subsidies if sheep were feeding the nation. But they’re not. Scots eat less lamb than the English or Welsh, while overall meat consumption continues to decline. Even if we only ate sheep meat produced in Scotland, domestic demand would still only account for 31% of all the prime lamb produced on Scottish farms, and 58% of all the sheep meat processed in Scotland. We could cut stocking levels by over 40% and still produce all the sheep meat we consume.

So we don’t depend on current sheep densities for our national food security. But we do depend on imports for other essentials like timber. If the security of our resources is a factor in decisions about land use, it’s surely worth considering whether sheep destined for export are worth more than timber we need at home. Or whether some land, in our national parks for example, might deliver alternative benefits – such as resilience to flooding or greater biodiversity – if it supported fewer sheep.

And what about the value of a sheep compared with the value of a wild animal like a lynx? There are now around 50 reintroduced lynx in Germany’s Harz Mountains, generating a reported £10 million each year for the local economy – or £200,000 per lynx. Over its lifespan the average lynx could generate more than £2 million. By contrast, a lamb in Scotland sells for under £150, a ewe for around £250, and a breeding tup for about £400. In simple economic terms, one lynx could be worth around 10,000 sheep – a reminder that while living with lynx might incur costs, living without them incurs opportunity costs too. And that’s before we even consider the more profound reasons people value charismatic wild animals.

‘Both sheep and lynx have important non-economic value for many people, deeply rooted in the different emotional, cultural and socio-ecological value systems we all cherish.’

Opponents of rewilding tend to dismiss the return of lynx to Scotland as ‘wholly unacceptable’, as if any level of livestock predation is unthinkable, rather than the international norm. Conversely, lynx advocates sometimes downplay the risk of conflicts, as if individual sheep losses hardly matter. Both positions are extreme, ignoring the reality that both sheep and lynx have important non-economic value for many people, deeply rooted in the different emotional, cultural and socio-ecological value systems we all cherish.

Finding a compromise that acknowledges and at least partially accommodates all our different values won’t be easy. But if we choose to, we could coexist with lynx, eagles and sheep. Many other countries do. Precisely how we might do so in Scotland has yet to be determined, but various systems for living alongside predators already exist in Europe. We have an opportunity to borrow from all that experience, to design a model that works best in Scotland, for Scotland.

Charismatic wildlife is increasingly used to promote nature-rich rural areas, such as the town of Bad Schandau in Germany.

There are lots of moderate, nature-friendly farmers out there. Many are open to compromise, recognising that a thriving agricultural sector can – indeed must – coexist with nature recovery. But when farming organisations and their political allies pitt food production against nature recovery, they present a false choice. And if we must pick one or the other, why sacrifice the many benefits of healthy ecosystems just to raise more sheep than we need?

‘If we choose to, we could coexist with lynx, eagles and sheep.’

For reasons we can only speculate on, John Swinney felt moved to tell the recent National Farmers Union Scotland conference that a lynx reintroduction would not happen under his government. This, despite his own government’s claimed commitment to restoring nature and reversing biodiversity loss. How he reconciles these two positions is unclear, but what is clear is that a just transition to a greener future will only be achieved when politicians recognise that both lynx and sheep have significant, and in many ways incalculable, worth. Stretching far beyond basic economics or even complex ecology, this worth is informed by the deeper influence these animals have on our lives and how we experience the world. Excluding either would be a failure to compromise, robbing one group or the other of some key part of what makes our lives worth living.

And who would vote for that?